One-dimensional humans: the curse of single sign-in apps

Have you felt like you don’t have enough control over what you reveal to people because of the way apps are designed today? Have you ever wanted to sign into an app with a different account than your primary account? This article is for you.

Thanks to my trusty tribe of privacy nerds for their comments. Will Scott, Park Feierbach, Mark Tyneway, Oskar Thoren, Taylor Hornby, Kyle Manna, and Anon Aaron.

Who needs control over their identity?

First, some vignettes:

Samantha is a computational biologist who develops new proteins for longevity research. In addition, she has a strong interest in energy healing arising from a deep meditation practice. However, this interest may be seen as too “woo woo” for her industry. As she is relatively early in her career, she is afraid that her scientific work will be discounted and her career held back. Therefore, it is important that she can keep separate (and private) her identities in the research and energy healing communities.

David lives in a country which is undergoing sudden and violent political change. He works at a government desk job but becomes active in nonviolent protests and assists with organization. It’s unclear which side will prevail, so to him, it’s important that he keep his identity secret.

Miriam works as a software engineer in the cryptocurrency industry. She contributes to several projects, sometimes using her public identity and sometimes participating as an anonymous contributor. For projects where she contributes anonymously, people often assume she is male, and she notices they are more open with sharing information and soliciting her to apply for new projects than if they know she is female. To sidestep the gender bias inherent in her industry, she would like to keep her public and anonymous identities separate from each other.

Cherie is a victim of domestic abuse. She is trying to get help from social services to exit the relationship, but her two young children make the process more complex and time-consuming. She needs to keep her communications with social services secret from her partner.

The above vignettes, tinged with different levels of conflict, are fictional accounts of why it’s important to have control over one’s external identities. You may relate to some of it. I certainly do.

Today’s apps strip us naked, reducing us to one-dimensional humans

Something that has bothered me is that many mobile and web apps today are designed to be used with only a single identifier. For example, Signal, Obsidian, and ClickUp, Asana, Airtable, in the messaging and productivity app categories, assume that you will only log in with one identifier. Even in scenarios that are not conflict-laden, many others have also voiced their desire to switch between accounts easily.1

This means I’ve had to choose among: (a) reluctantly using the same identifier for different identities, thus failing to separate my identities2, (b) accepting that I have to switch log-ins when I’m switching identities (the extra friction typically resulting in me involuntarily reducing participation in one identity), or (c) carrying around more than one device (mobile phone) so that each is logged into a specific identity.

A note on terminology: I refer to “Identity” here as one facet of a person. For example, someone could have two identities, one as a computational biologist and the other as an energy healer. “Identifier,” in contrast, is the information that identifies a person to a service, such as a phone number or email address. You reveal your Identifier to people with whom you communicate or collaborate via apps.

Practically speaking, it’s easier to be a one-dimensional human, so that one facet of life doesn’t interfere with others.

Don’t have fringe hobbies, don’t have fringe viewpoints, go with the flow of whomever has the most guns. Nevermind that the internet was built by hobbyists, yoga was once considered occult, and freedom in many countries today was wrested from people with lots of guns (ahem, colonial history).

However, over the years a minority of apps, such as Notion, Slack, Telegram and most email clients (Apple Mail and Gmail for example) have added multi-account features3. You can easily sign into multiple accounts, each tied to a different email address or phone number.4

People work and live in different communities. Today, as conflicts multiply within and between communities, it has become increasingly necessary to separate our identities to be safe and to preserve our freedom of expression. We should be able to use unique identifiers to interact with any application.5

Just like Dark Mode became a de facto standard because we clamored for it, I want to see apps comply with standards for facilitating multiple sign-ins.

Freedom to reveal or conceal: a rubric

How do we know if an app is well-developed for the multiple sign-in use cases we highlighted?

I’ve developed a framework to evaluate apps on this basis, which I’m calling the “Conflict-Ready App Evaluation Framework (CRAEF).” CRAEF enumerates a set of features that allows us to exercise control over identity-disclosure6. I’ve written the features as user stories.

Identity

I want to use a single device (phone or laptop) to interact with different people using different identifiers (accounts), so that I can keep my identities separate

I want to choose which identifier I use (e.g. phone number vs email address)

Privacy & Security

I want to create an account without the app disclosing that to all users that have my identifier7

I want to disclose only a chosen username to others (not my identifier), so I can keep my identifier private8

I want to hide my accounts behind additional authentication (e.g. biometrics or PIN/password), so that if someone has access to my phone, they cannot automatically access the contents of the account

I want to hide certain chats or files, so that if someone has access to my phone, they cannot see specific content

I want to hide the fact that I have multiple accounts on the same app, so that if someone has access to my phone, they see only the accounts that are not hidden9

I want to turn on auto-delete (aka self-destruct) features, so that I don’t have to worry about permanent information disclosure or exploits of the server’s database

I want to turn on or off edit features, so that I can choose between convenience (editable) and truthfulness (non-editable)

I want to use end-to-end encryption so that my messages cannot be intercepted during transmission nor decrypted on the app’s servers

(When e2e is enabled) I want to verify that end-to-end encryption is active, so that I don’t need to worry about attacks or privacy invasions

I want to self-host the data easily, so that I don't have to worry about privacy attacks.

If 2FA is required, I want to be able to use something other than phone number as my 2FA device (e.g. hardware tokens, passkeys)

UX

I want to group contacts into categories, so that I can better manage the information that I share (e.g. share posts 1:1, in groups, or with everyone)

I want to add notes to contact entries, so that I can better manage which identities I disclose or keep private (e.g. note which users know more than one of my identities, e.g. a coworker with whom I also share a hobby)

I created a repo on Github so that others (you!) can contribute to the list. Please fork and contribute.

These features carry different weights in different use cases. The personalities in the vignettes at the beginning all care about using different identifiers, but differ in how much the other features matter to them.

Samantha (scientist with alternative hobby) and Miriam (female software engineer) care more about keeping track of who knows their identities (features under UX section) and less about hiding accounts behind authentication.

David (government worker and newly an activist) cares more about end-to-end encryption and less about control over edits.

Cherie (victim of domestic abuse) cares more about hiding logins and specific content than about self-hosting.

Evaluating popular apps

Now that we have a framework for evaluating how conflict-ready an app is, we turn to evaluating specific apps.

Here we evaluate apps in three major categories: Messaging, Productivity, and Social Media. (Green indicates the feature is available while red indicates the feature is unavailable. Yellow indicates that the feature is available in a limited way.)

Overall, none of the messaging apps excels more than a few of the features. However, Signal and Telegram rank highest.10

In the Productivity category, Obsidian and Skiff11 are much more identity- and privacy-respecting than apps like Notion. However, this category fails to impress.

See here for the full spreadsheet. I’ve added comments to some cells explaining their rating.

Going back to the vignettes we started with, Samantha (scientist with interest in energy healing) and Miriam (female software engineer) are both best served by using two separate accounts on Telegram, allowing them to separate their interactions with different groups of people. David (government employee and activist) is better served by Signal because it is critical that his messages are always encrypted12. Cherie can be equally well served by Telegram or Signal, as both allow her to lock the app behind additional authentication and have message auto-delete features.

Embedding identity freedom into product design

The state of the most popular communication and collaboration apps today leaves much to be desired from an identity and privacy perspective. Admittedly, using identifiers tied to people is often the strongest protection against fraud and abuse. But we are making tradeoffs that are becoming increasingly unpalatable as the world changes.

We have a moral imperative as product creators to build apps that serve humanity and the ability to live freely (within the constraints of bottom lines). Companies should go beyond using "inclusion" or “accessibility” to virtue-signal and instead embed it into product design.

The commercial reality is also that as the world splinters and we find more reasons to disagree than to agree, we will need and demand more choice in identity disclosure. As we increasingly live our lives online, we must acknowledge that just as we maintain distinct personalities for different IRL communities (family, work, church, pickleball team?), we should be able to do the same online.

Otherwise, diversity of thought suffers because we have to squash all our personalities down to the lowest common denominator. Who wants to live in such a world?

Let’s build for freedom.

Author’s note: this article is NOT about privacy at all levels. It’s not about achieving maximum (cyber)security. It’s not about being safe from hackers, poor corporate data governance, government subpoenas or the NSA. Instead, it’s centered on being able to control what people can discover about you outside of what you actively allow them to. I am also not treating another concern, which is that if you sign in with several accounts within a single app, companies will be able to link your identities, and either hand that info to others (including marketers and future acquirers), or lose that info to hackers.

Aside: If you have web dev skills, I’m looking for someone to collaborate with to create an interactive web app version of this evaluation framework. The end goal would be for someone to say, “I want a messaging app that can do x, y, and z. Which apps satisfy these requirements?” Conversely, someone could say, “I was told that Telegram Is a good messaging app. What can or can I not do with Telegram?” These two people could use the web app to answer these questions interactively.

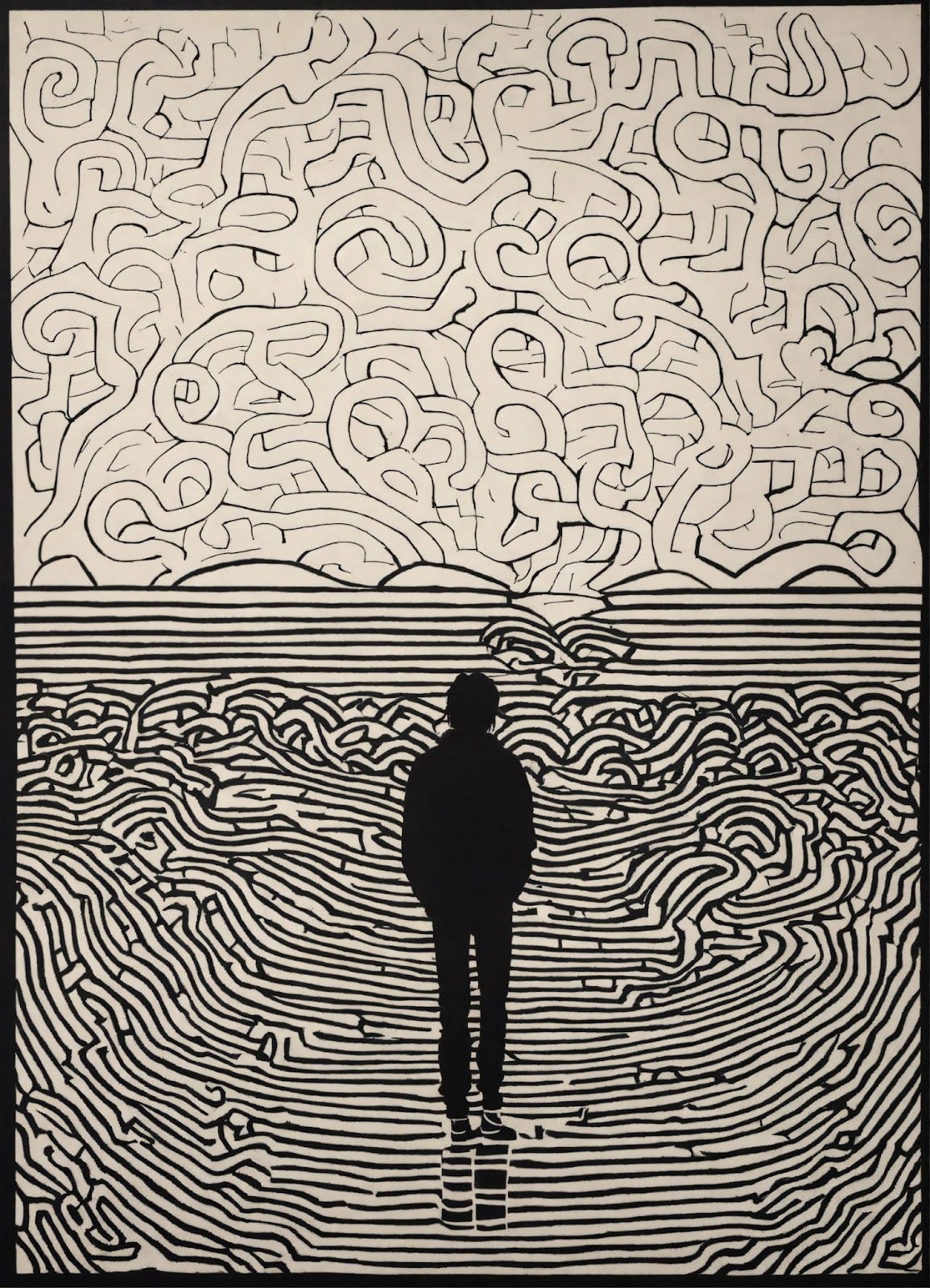

Photo credits: all photos in this article were created in Dream Studio by Stability AI.

Some apps have made multiple accounts only available on certain clients. E.g. on Clickup, multi-account sign-in is available on the desktop app but not the mobile app nor the browser. And on Whatsapp, two-account sign-in is available on Android but not iOS.

“Failing to separate” means that people in one community could discover that I am a part of the other community, which may be embarrassing, damaging, or even dangerous. In any case, it takes away my prerogative to selectively reveal different aspects of myself to different groups of people.

Sometimes multi-account support is limited to Personal and Work accounts.

Here is a not-serious but very important use case: when I match with someone on a dating app and we decide to move off the app to message, I first share a Telegram account that does not have my full name in the account ID. Only after we meet up a few times and I determine that they’re not unstable and that I don’t mind them googling me to identify me professionally do I transition over to my regular account, one that I check more regularly. It’s definitely saved me from some flaky weirdos.

I avoid using the tech-centric word “users,” and instead use “we,” “I,” and “us,” because product and engineering people sometimes need to remember that the “users” of their products are humans, with real human needs and changing social behaviors. Jargon in any industry often makes us forget that the ultimate beneficiary - or victim - of product choices are meatspace homo sapiens.

In fulfilling the goal of securing identity, inevitably, privacy and security are prominent ancillaries.

Telegram in particular fails at this. They notify everyone who has your number when you join Telegram.

Telegram excels here, being one of the few applications that allows you to share just your chosen name and not your identifier.

I don’t know of any apps that do this today, however an analogous approach might be the Ledger hardware wallet’s “plausible deniability” feature, which allows you to log into a secondary wallet when you key in a secondary PIN. Scenario: someone holds you hostage and forces you to unlock your Ledger device; you enter your primary account PIN which contains a small amount of funds, while your larger secondary account is hidden from view. In our context, the app could be unlocked with two PINs, with only one PIN displaying sensitive accounts.

Signal announced on 20 February 2024, while I was making my final edits to the post, that they were launching their long awaited numberless feature. It’s still in beta but very exciting!

Skiff announced they are being acquired by Notion in February. From the positive framing that both companies put out, I (wrongly) assumed that Notion would simply run Skiff as a separate product, so I included them in my analysis. However, current reports evidence that the entire Skiff stack will be (unceremoniously) sunsetted.

Prior to Signal’s announcement on its numberless feature, two Telegram accounts would have worked better for David than one Signal account, even if Telegram does not have default end-to-end encryption. This is because on Signal his phone number would be visible in any activist groups.